Nelson: The tone of your questions or requests in Tree Talks contrasts the tone of such a law; for example, when you say, “Tell me about your experience …,” implicit is the inherent validity and importance of another being’s existence. I feel a through-line of compassion in these conversations; you ask, “What would make this a better place for you?,” and you thank the blue palo verde for its shade. But I do sense that the conversations were had in a cultural context that has foregrounded certain fears and suspicions: You ask the one-seed juniper, “Do borders have a meaning for you?” Thinking symbolically about SB 1070 and the several copycat bills that have followed, I can read much into your questions for the ponderosa pine: “What is it like to be in a fire? What is it like to withstand a fire?” These are questions that I hope become less not more relevant in 21st-century United States. Fear always has us imagine more flames.

Burk: I appreciate your reminding me of the gentleness of some of the questions. What I find myself remembering after the fact is how intrusive they seemed to be. You’re pointing out that asking questions can be a way of showing respect. One of the questions I asked the Goodding willow in Patagonia-Sonoita Creek Preserve is, “You are known as a tree of refuge. What do you shelter?” That question also feels related to SB 1070, because of the idea of sanctuary, and it could also be read as a gentle question, in some ways. Very large fires are one of the consequences of climate change in the Western U.S., so in a literal sense, questions about fire are likely to remain relevant. I like your use of fire as an analog of fear, though—because fear is ineffable, yet is able to spread widely and overpower...? Fire can regenerate landscapes. I don’t think fear can regenerate anything. But there is a value in standing up to fear, and humans can do this in an active sense.

Nelson: One of my favorite stories from childhood is Dr. Seuss’s The Lorax, in which the title character says repeatedly, in a time of capitalist greed and environmental catastrophe, “I speak for the trees.” I appreciate your work, Wendy, as an acknowledgment of the vital importance of the flora and, more broadly, as a critique of human self-importance. Regarding our having ushered in the Anthropocene—and the ominous implications of that fact—of what are you optimistic, and where do you direct your hopes?

Burk: Every morning feels like a new opportunity to be optimistic. It just seems to be related to the experience of waking up and living another day. Maybe Tucson's weather plays a role in that experience for me. When I wake up, the sun is usually shining, and if it’s not, the overcast sky is calm and different and beautiful. I’m also not attracted by apocalyptic thinking. Let’s keep at it. We don’t have to bow down to hatred and willful ignorance.

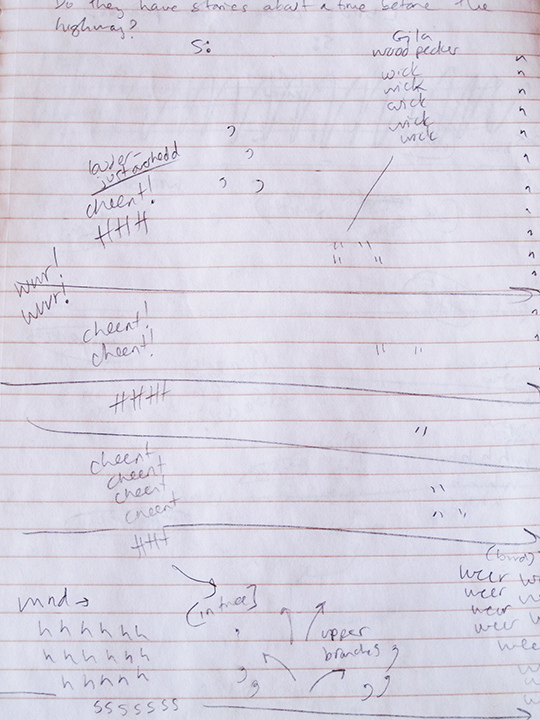

Nelson: I’m fascinated by your typographical innovations in these interviews. You’ve used various font sizes, symbols, special characters, punctuation, and (sometimes) words to convey the aural reality at the time of the conversations. Will you tell us about those challenges and decisions?