Interview with Samuel Ace —

April 22, 2014

Samuel Ace is the author of Normal Sex, Home in three days. Don’t wash., and, most recently, Stealth, with Maureen Seaton (Chax Press). He is a recipient of a New York Foundation for the Arts grant, two-time finalist for a Lambda Literary Award in Poetry, winner of the Astraea Lesbian Writer’s Fund Prize in Poetry, The Katherine Anne Porter Prize for Fiction, the Firecracker Alternative Book Award in poetry. Most recently his work can be found in Aufgabe, The Atlas Review, Versal, Rhino, Volt, Mandorla, Black Clock, The Volta, and Troubling the Line: Trans and Genderqueer Poetry and Poetics. He lives in Truth or Consequences, NM, and Tucson, AZ, where he serves on the board of POG: Poetry in Action, a poetry collective and reading series.

Christopher Nelson: When you consider your poetic concerns over the years, what has remained constant and what have you left behind?

Samuel Ace: I think that’s a great question. In my current work, I feel like I have returned to something that interested me from a very young age, and that is music. In recent years, I have been led by the music of the line, following language, allowing bits and pieces of narrative to appear and disappear. I was trained early on as a musician, a pianist. Music, in a way, was my first language, and I always looked at poems from the point of view of music. My father worked in construction, but he was a reader; our house was full of books. I remember finding a book of Yeats when I was maybe eleven or twelve. I didn’t understand much about what I was reading, but I loved how the words sounded in my mouth. I started copying out his poems, then I started to write my own poems as if I was writing in the music of Yeats’ language. I wish I still had those poems!

Nelson: Much of your writing is prose poetry. How does your music work in that form, or is your engagement with prose poetry a stepping away from your interest in music? I think most people would consider it a less lyrical form.

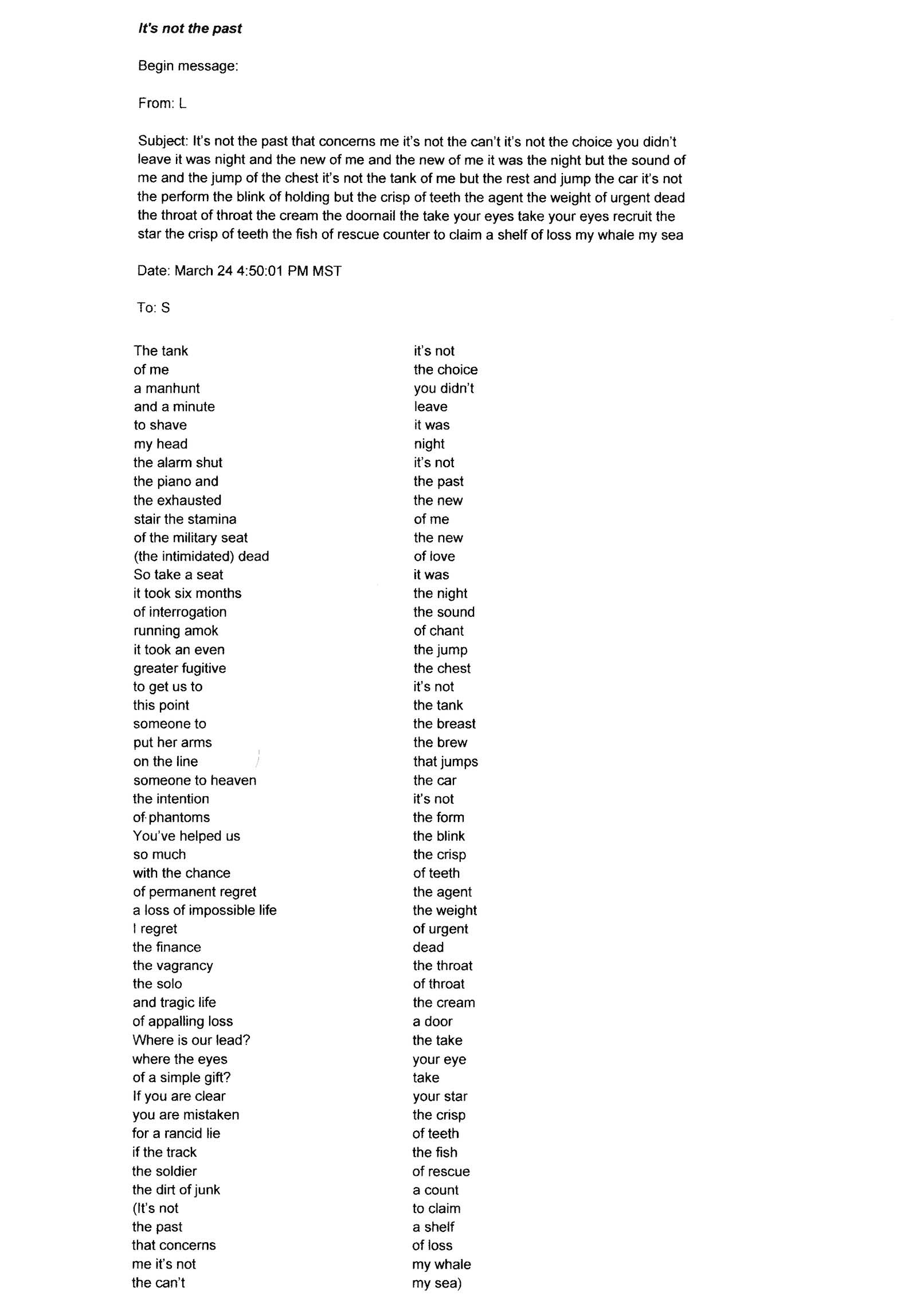

Ace: I think the opposite. Very much so. I sometimes find lineated poetry somewhat claustrophobic. I don’t always like to be directed as to how to hear things or how to read a line. I often read other poets out loud, and I find that grammar, line breaks, even spaces in the poem, direct me in a way that I often rebel against. I see the text block as being very layered and profoundly rich. Where all the possible voices can happen at once. And yes, you can read my text blocks through linearly, but I avoid punctuation; where the line, delineated by space between phrases or words, is meant to be a suggestion only. When I read the pieces out loud, the spacing and rhythms change from performance to performance: where I breathe or don’t breathe, or where I choose to end a phrase or open up a phrase. I think of the prose poem as a very musical form, one that feels more open to interpretation than lineation. That being said, in the “Secrets” section of Stealth—the abecedarian I wrote with Maureen Seaton—the poems authored by me are the short lineated poems. It was the first time in a long while that I had written short poems. Currently, in the epistolary poems of my new manuscript, the poems consist of text blocks combined at times with very short enjambed lines.

Nelson: I’ve heard you read some of those epistolary poems (one of which is included at the end of the interview). Are the people in dialog your two selves, or current and prior identities: Samuel Ace and Linda Smukler?

Ace: It’s always a dialog with oneself, if you’re a poet, I suppose. That strange conversation that goes on in our heads and bodies and in our speaking lives. But, yes, I think so, Sam and Linda, in a loose fashion. In many of the poems, I am in collaboration with myself, using revision in the broadest sense, a burrowing in, an excavation, an improvisation.

Nelson: Are there two fixed characters in dialog, or do the correspondents change?

Ace: There are two fixed characters, but they’ve been reduced to initials. And the initials have to do with how the body of the text is written; one of the writers prefers the prose poem, and the other one dances around with the shorter, lineated lines.

Nelson: Let’s talk about your photography. Is there a relationship between your written art and visual art?

Ace: An image may be a portal to a poem, but not in a very direct, descriptive way. I am a very visual writer. Language contains visual repercussions all over the place for me. I will often see something visually as I write: a color, an image, or an emotion. I have a visceral visual response. A form of synesthesia I believe. Response may be the wrong word—I have a visual impulse in language. I was trained as a painter. I went to graduate school for a short time for painting. When I moved west from New York, in 1997, I had just bought a large-format camera. I focused on the visual, on taking photographs, as a way of dealing with finding home here. I don’t have stereoscopic vision; I use one eye at a time, mainly my right eye. I use my left eye mostly for peripheral vision. I’ve learned to compensate for not having depth perception: I can drive a car. But I honestly don’t even know what it would mean to see three-dimensionally. I think I flatten things into two dimensions automatically. Just the act of looking has always been important to me. I started photographing when I was young. My father had a darkroom and I learned how to use that. I like having a camera in front of my eye, I find that there’s a space or zone of seeing, similar to taking notes, but an active way of looking.

Nelson: In your landscapes there’s often some human element—a trailer, a silo, signage—that stands in contrast to the vastness and purity of the natural landscape. What fascinates you about including these human structures?

Ace: I’m just really drawn to them. It’s probably a way of organizing the landscape or the space of the frame. It’s a way of locating, and creating scale in the vastness. The one photograph I took at the Grand Canyon is of a red firebox. It takes up the whole frame, a three-foot structure that looks like a house.

Nelson: It sounds like it’s more about composition than narrative.

Ace: Perhaps. I try to stay in an instinctive place about it all. Besides landscape, I’ve also focused on other kinds of subject matter. For many years, I have done an ongoing meditation on objects, two- and three-dimensional, found in thrift stores, swap meets, people’s houses, on the street.

I spend a lot of time in Truth or Consequences, New Mexico, where there’s an annual small-town parade with lots of floats and fire trucks. Miniature cars driven by the local Shriners. I’ve photographed the parade over the course of several years. I’ve taken many of the photos during the pre-parade, while people are setting up for the main event. ROTC kids and band kids and dancers on floats—the extraordinary beauty of all who are involved. I suppose there’s narrative in that. It’s a way of looking and a way of connecting to something very human.

Nelson: Earlier, you mentioned Stealth, which you wrote with Maureen Seaton. Tell us more about your collaborations. How have these affected your style and what have you learned from the processes?

Ace: After finishing Stealth, Maureen and I have continued to collaborate. We’ve recently finished a three-volume work, called Portals, and have started on a more prose-like project. And for about the last six months, I’ve been doing a mutual interview/review/writing collaboration with j/j hastain, a Denver writer. Collaboration has been extremely important for me. I find that working closely with someone else’s voice allows me to get out of my own way, out of my own tropes—those habits of language that become too familiar and reliable. Collaboration has been very important in helping me reach what’s possible beyond what I know.

Nelson: How did your transition affect your writing? Did it give you permission to explore subjects differently?

Ace: Very much so. A lot of the material for Normal Sex, my first book, came out of a workshop that I took with Gloria Anzaldúa in New York City. I had been living in the city, working endlessly at many odd jobs to earn a living. I sold office supplies over the phone, worked as a production assistant for commercial film companies, did layout for a typesetting company. At one point, needing to take a break, I decided I would travel as far north as I could along the east coast. I hitchhiked through Vermont and Maine. I took boats up through Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, and on up to Labrador. When I got back from that trip, I was at a total crossroads in my life. I had been offered a job teaching music in Labrador, and had also been accepted by the Peace Corps. They wanted to send me to Thailand. I was trying to figure out what to do. Carl Morse, the editor, along with Joan Larkin, of the anthology Gay and Lesbian Poetry in Our Time, curated Open Lines, one of the first reading series for lesbian and gay authors in New York City. That’s where I first heard Gloria read, and she completely blew apart my head and my heart. After her reading, I acted on impulse, and asked her if she had a workshop going. She said yes, so I joined. The workshop met weekly at Gloria’s home in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. “Tales of a Lost Boyhood,” from Normal Sex, came out of that workshop. Those prose poems were based on my gender dysphoric experiences when I was very young. It was through writing, and that workshop, that I started to really deal with my gender identity; writing led me to where I could say things that I was too terrified to say in other places. I didn’t transition until after I moved to Tucson, even though the impulse had been with me my whole life. And in some ways I find that, since my transition, the issue of gender has disappeared. It isn’t the driving force anymore—not that it’s not there. But I aspire to fluidity in myself and fluidity in my work, so there are times I’ve written about gender very directly, and there are times I write about it slant. There are also times when the gender will change within a poem, or appear and disappear. It’s completely dynamic.

Nelson: One of the things I enjoy about your work is that it’s not just an exploration of gender but identity more broadly. It seems that our culture encourages a fixed identity, and that for most people shifts in identity are accompanied by anxiety and resistance.

Ace: I believe it’s the human condition to want to find a place of safety. Our culture is so demanding of certain kinds of conformity, and there is the projection of these seemingly solid forms: male/female binaries and what it means to be feminine or masculine. I believe that we’re all carrying around masks. As we gather experience we kind of link our experiences into forms: I’m looking at a chair and I say, “That’s a chair.” But as we get older, the things we perceive are less and less new, our forms become more fixed and expected. We start to look at the world with less and less awe. I want to fight against that. I want to see things as if I’ve never seen them before. I don’t accept the mask I might see—or assume exists at first glance—in someone’s face or in the clothes they wear. I want to connect spiritually to what lies beneath all of that. Even though I now carry around this whole other mask—one that reads male, along with the beard and a balding hairline—I would hope that I always challenge that mask to fall away. I want to be aware and careful of the privilege that I now carry as a white man. I grew up female, experiencing the extreme and pervasive patriarchy of our culture, and I need to hold onto that awareness even though I now exist in this male-appearing, less liminal, embodiment. And privilege functions just as strongly in the institutional world of writing as anywhere else. One needs to be aware of it as a force.

Nelson: It’s amazing that you’ve been able to see the world from two gendered perspectives.

Ace: Multi-gendered. … For me it’s important to acknowledge too the things that get left behind. I’m not sure I could have known this at the outset. The motivation to transition was very primal for me, germinating when I was very young. I read literature that talks about the trauma embodied in the act of passing. There’s a Langston Hughes story I go back to over and over. “Passing,” in The Way of White Folks, is written in the form of a letter from a young man to his mother. He is writing to thank her for not saying hello or acknowledging him as they see each other while walking down the street. He is a black man, passing as white, walking with his fiancée, the white daughter of the white man he works for. Neither the fiancée nor the boss knows that he is black. Through that story you realize that he’s given up his entire family, his culture and his history, in order to have any degree of what he considers success. It’s a heartbreaking story of survival and loss. I am not equating my history with the history of the narrator of Hughes’ story. What was at stake for him as a black man in the early part of the last century was far greater than what was at stake for me, transitioning from white woman to white man. At the same time, as a lesbian feminist, I resonate with the loss and the distances created by the act of passing.

I have been fortunate to have been able to create and find safe spaces within myself and my communities, places where identity can be fluid and where the masks can really slip away. That internal safety is important and is often so hard to come by. Sometimes it comes and goes. And as a writer I’ve felt grateful for so many gifts—one of the earliest gifts for me was finding Gloria at the time and place I found her. We do get these awakenings if we’re open and willing to follow them. If we have the courage to follow, I believe that we can be channels for what the universe is trying to tell us. The writing has often taken me to places that I didn’t know I could go. If one listens hard enough, the path is there. It really is. Often the fears and hesitations that hold us back as writers—or in our lives—are like that man behind the curtain in the Wizard of Oz; when you part the curtain and take away the sound effects, they’re really human sized. Sometimes those human-sized fears come from deadly origins. But often they’re just fears. Like vapor. And until you step through them, you don’t know.

Nelson: Wonderful. Thank you, Sam. Let's conclude with a poem you wrote, originally published in Versal 11.