Interview with Jordan Stempleman on String Parade —

December 30, 2008

Jordan Stempleman is the author of Their Fields (Moria, 2005), What's the Matter (Otoliths, 2007), Facings (Otoliths, 2007), and The Travels (Otoliths, 2008). String Parade is available here from BlazeVOX. Visit Jordan's blog, Growing Nation.

Christopher Nelson: Each poem in String Parade is dedicated to someone; at times I felt that the dedications were like invocations. Tell us about the dedications.

Jordan Stempleman: I knew I wanted to have a book of poems that already had a number of readers, that they were written to be read, handed off you could say. I modified O'Hara's notion of "Personism" a bit, since some of the poems were to people I will never meet, while others were to friends, acquaintances, those I deeply admire, that all share the same name. Others were of course for those people I know oh so well and that often saw their poems well before the book came out.

I like how you call them invocations, since I was often sending waves to a reader who might not otherwise be found. Dorothea Lasky gets it, really gets it, when she writes in her reaction to the book: "Here in these poems, Stempleman creates a spectacle of dedication for the everyday people he loves, which by the end of the book, we realize is all of us." I was hoping that someone who read this book would see that if the book were to go on indefinitely, their name would most assuredly appear with a poem dedicated to them.

Nelson: There are a variety of forms here: prose poems, poems in fragments, poems in parts, single- and double-spaced poems. How do you determine the shape a poem will take?

Stempleman: I just realized the other day that String Parade was the final book in a trilogy, which includes two earlier collections (What's the Matter and Facings), where I allowed for any and all influences of form to be allowable, usable, and ready. As a younger poet I was often so uneasy about the "what had happened," so much so that I often ended up not writing much of anything. I thought it had to look new. Sounding new is sounding like oneself. But looking new—I just didn't know how formally that would ever come about. So with What’s the Matter and ending with String Parade, I finally erased the notion of formal inventiveness and concentrated more on content—search for what I couldn't say, what was often ungraspable otherwise, etc. It made for poems! It allowed for the unreachable, just out of sight speech that makes up my poems to find a place to live. Often the first line would dictate the form of the entire poem. So that I like to think that the language of the thought built the space only it could comfortably occupy to come out and take the poem as its form of preference. Does that make sense? The song found in that first line then said "I need more space to breathe, give me a double spaced line" or "Keep me at a clipped, W.C.W/Creeley line" or whatever. I never would come to the time to write a poem and, before the first line was what it became, determine the form of the poem.

In the last two collections I've written, the complete opposite is true, which in a strange way is actually less hectic than the old way I composed a poem. I now either write in a boxed, even line-length form, or in a half-kidding Projective Verse. I guess I might say I can hear myself better now than I ever thought possible. Somehow all the voices that were once so numerous have meshed into something much more singular and consistent.

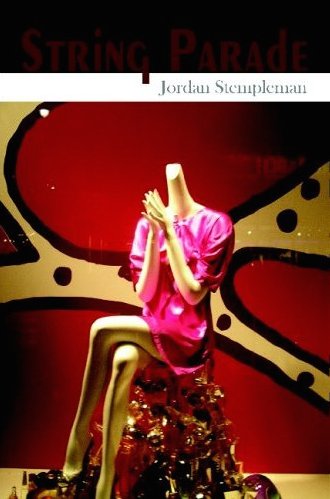

Nelson: The cover is so evocative: an elegant, headless mannequin on a heap of rubbish. Why was it chosen, or how do you consider its relation to the poems?

Stempleman: I love that photo. Geoffrey Gatza, the wondrous editor of BlazeVOX sent me a number of photos he had taken to choose from. I was immediately drawn to its headlessness, its posture, and the glow it commanded from all the glass junk. Because as we all know, glass junk is nothing like other kinds of junk. It tends to respond to a cleansing so much better than other garbage.

As it relates to the poems, well, I like thinking that where the head belongs, we all belong—each of our faces belong for however long, giving room to the next person in that line. It reminded me a lot of the earlier sonnets from Shakespeare, where the beauty seemed intact above the decay through remembrance, through the presence of another or the active mind of one thinking of that someone else.

Nelson: How do you see String Parade when compared to your previous books—formal developments, thematic interests, motifs, etc.?

Stempleman: I think I pretty much did what I could do with this question in my earlier response, but in regards to motifs, well, all the poems were written with that which was near. Which of course means in the room, or on my mind, or in the foreseeable future. I am at my worst and sometimes at my best, devoted and attentive to my surroundings.

Nelson: There’s a comical tone in some of these poems. What about humor in your poetry?

Stempleman: When it happens, I'm relieved. I think it's easy to become overly serious in what Williams went into poetry for—the warmth and the loneliness. But with Williams, especially the earlier work from Al Que Quirre, Sour Grapes, Spring and All, etc., there's so often this wry sense of availability he displays. It's as if faced with the vastness of possible outcomes and reactions to single events, he is able to often find the best reaction and temperament to ease us all. What a good doctor! I in no way look for humor in the same way that I believe Williams does, since I know that mine is cut from a more grotesque cloth. It is more of an end of the night humor. Everyone's tired, open, and forgetful enough that whatever's said be understood as not that uncouth upon reflection on the following day.

Nelson: Are there any traditions or aesthetics that you’re deliberately playing forward? When reading these poems I thought of the Objectivists from time to time.

Stempleman: I wouldn't say I'm playing any particular aesthetic forward in these poems, but rather navigating existing aesthetics, mining preexisting aesthetics that I thought could aide in my acceptance of the vast number that are currently available for our consumption, er, communication. In my bookThe Travels I was very much attempting to have a go at an imagined history with an Objectivist weight of words, rather than of experienced experience. I was definitely after the experienced word. The poems in String Parade felt much more like the cacophonous 20th century of postmodern occupancy. We're all(right) and we're all speaking up and over ourselves at once. Since to go silent is a complete waste of precious resources. String Parade, along with the other two books, were a room full of different perspectives asked to see through to some other side.